Vocal Fold Granuloma

David Goldfarb, DO Princeton, New Jersey

Figure 1. Granuloma interfering with phonation when the mass slips subglottically during adduction and causes failure of glottic closure (upper left). The mass can be seen in various positions with relation to the airway and other vocal fold, depending upon the degree of adduction (upper right, and lower figures).

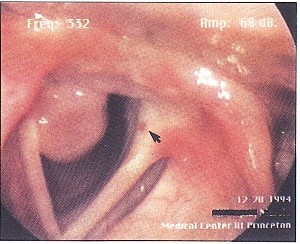

Figure 2. Even in wide abduction, the mass partially obstructs the airway, although the obstruction is not clinically significant. A contact hematoma is visible on the other vocal fold (arrow).

The patient is a 38-year-old female homemaker who developed progressive symptoms of cough, hoarseness and intermittent shortness of breath one month after intubation for emergency surgery . She had no significant medical problems, and her only medication was a multi vitamin. She smoked cigarettes for 10 years, but quit 13 years prior to this evaluation. On examination, the patient had a breathy voice. A large pedunculated mass was attached to the right vocal fold. The mass was attached to both the inferomedial aspect of the right posterior vocal fold and the medial aspect of the right arytenoid. A small hematoma was noted posteriorly on the left vocal fold as well, secondary to constant trauma from the right vocal fold mass. However, the mass interfered intermittently with the vocal fold approximation during phonation (Figure 1) and partially obstructed the glottic airway during inspiration (Figure 2). The arytenoids were mildly erythematous in color. True vocal fold color was other wise normal. The mass was removed by microscopic direct laryngoscopy with CO laser. The histopathology was remarkable, as expected, for granuloma. The patient's symptoms immediately resolved, and she has not had any further problems.

Photography for this series is sponsored by Passy-Muir Inc., manufacturers of the Tracheostoiny and Ventilator Speaking Valves. For further information, please call 1-800-634-5397.

ENT-Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, March 1996

Laryngeal pacing as a treatment for vocal fold paralysis

We summarize etiologies of vocal fold paralysis and current treatments.The recent literature involving electrical stimulation of the larynx is reviewed. Four canines were involved in a study to test a new laryngeal pacemaker system. This system was used to stimulate both the lateral cricoarytenoid and thyroarytenoid muscles. The data are taken from two of these canines. One of the goals was to stimulate the paralyzed side of the larynx based on the activity of the normal (nonparalyzed) side of the larynx. The best stimulation parameters for full adduction of the paralyzed vocal cord were 3–7 V, pulse duration of 0.5 ms at a frequency of 84–100 Hz. Principles for electrode design and electrophysiologic parameters pertaining to laryngeal pacing are discussed. We believe that unilateral vocal fold paralysis may someday be treated by stimulating the paralyzed lateral cricoarytenoid and thyroarytenoid muscles to move in synchrony with the normal, unparalyzed, lateral cricoarytenoid and thyroarytenoid muscles.

Recurrent Rhabdomyoma of the Parapharyngeal Space

David Goldfarb, DO, Louis D. Lowry, MD, and William M. Keane, MD

Benign skeletal muscle neoplasms are rare, especially when compared with their malignant counterparts. Rhabdomyomas have been reported to account for only approximately 2% of all striated-muscle neoplasms.1 Although it is difficult to know the true incidence of this rare tumor, up to 76% of reported non-cardiac cases have been found to occur in the head and neck region.2

Rhabdomyomas can be subdivided into different groups, based on clinical and morphological differences. The purpose of this paper is to share a unique case presentation of a man who developed a recurrence of a parapharyngeal rhabdomyoma 25 years after primary surgical excision. This paper will review the literature and discuss presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, histopathological findings, and treatment.

Case Report

The patient is a 64-year-old white man, status post-resection of a parapharyngeal space mass 25 years before our meeting him. The patient presented with a chief complaint of a mass growing in the left soft palate region, progressive in size over the last 6 months. The patient in our case report was 39 years of age when he was originally treated. He originally told us that he had a benign tumor removed from the floor of his mouth 25 years ago. We were considering a salivary gland tumor as the most likely culprit, because they are fairly common neoplasms of the parapharyngeal space.3 After checking the patient's records from another hospital, we learned that a rhabdomyoma was removed from his left parapharyngeal space. Our patient was free of symptoms until 6 months before our evaluation, when he noticed a mass in his left soft palate region. During the physical examination, a large mass was found deviating the parapharyngeal space, soft palate, and tonsil. The tongue base, vallecula, and hypopharynx were clear. Nasopharyngoscopy showed no lesions in the nasopharynx or larynx; the vocal folds moved well. The epiglottis, pyriform sinuses, and hypopharynx were clear. The neck had an old, healed tracheotomy scar and labiomandibulotomy scar. No evidence of cervical adenopathy, bruits, or tenderness was found. Neurologically, the patient had no focal signs and cranial nerves 2 through 12 were intact. The rest of his physical exam was unremarkable.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was carried out with MR angiography. Intravenous gadolinium was administered, and Tl-weighted axial and coronal images were obtained using fat suppression. The MRI scan showed a large, left-sided mass in the parapharyngeal space (Fig 1). with extension to the tongue base and left tonsilar fossa. The MR angiography did not show any major blood supply. Both the carotid arteries were shown to be patent.

The patient underwent a tracheotomy, labioman dibulotomy, and resection of the tumor. The mass was 13- to 14-cm in diameter and partially obstructed the oropharynx. The whole tumor was sent to pathology as one large bulk specimen. The surgical pathology report confirmed the diagnosis of adult rhabdomyoma.

Pathology

Gross Specimen

The specimen was brown, soft, and nodular. Sections were sent for histological examination. The brown color is thought to represent the high content of mitochondria.

58 American Journal of Otolaryngology, Vol 17, No 1 (January-February), 1996: pp 58-60

From the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck

Surgery, Medical Center at Princeton, Princeton, NJ; and the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA.

Address reprint requests to David Goldfarb, DO

Copyright© 1996 by W.B. Saunders Company 0196-0709/96/1701-0011

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma of the Mandible

David Goldfarb, DO, Diran Mikaelian, MD, and William M. Keane, MD

(Editorial Comments: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma may rarely present as an intraosseous focus in the mandible. The authors discuss the three main theories used to explain this tumor location. Wide local excision produced good results in this case.)

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is made up of epithelial and mucin-producing cells. The le sion originates most frequently in major salivary glands, usually the parotids.1 The lesion rarely appears as a central lesion in the jaw bone. The predominant locations in the mandible are the posterior alveolus, angle, and ramus.

The purpose of this paper is to discuss the clinical entity of mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the mandible, and illustrate it with a case presentation.

Case Presentation

A 49-year-old white man developed pain in the right lower mandible several years prior to seeking medical attention. He had recently been examined by his dentist and found on panorex film to have a lytic lesion of the mandible (Fig 1). He was referred to an oral surgeon. The third molar from the right side of the mandible was removed and biopsy results from adjoining tissue were remarkable for intermediate-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. The patient was referred for further evaluation and treatment. Metastatic work-up including bone scan, liver/spleen scan, and chest x-ray were all negative. His past medical history was remarkable for hypertension and an atretic right ear. The patient had no known allergies. The patient reported no tobacco use and only occasional alcohol consumption.

The physical examination showed a well developed, well-nourished man in no apparent dis tress. His vital signs were stable. His mouth was clear and no lesions were noted. The right lower third molar had been extracted and the overlying soft tissue had healed. There was some minimal swelling in the retromolar trigone region. On bimanual examination no palpable soft tissue masses were appreciated in the floor of the mouth region, base of tongue, or tonsillar fossas. A neck examination was negative for palpable masses. The rest of the patient's physical examination was unremarkable with the exception of an atretic right auricle.

The pathology slides were reviewed by our pathologist who concurred with the diagnosis of intermediate-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the mandible.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent an initial tracheotomy followed by a right modified radical neck dissection and resection of the angle of the right mandible with reconstruction using the right sternocleidomastoid muscle. The postoperative course was uncomplicated and he was discharged home on the eighth postoperative day.

Contents of the neck dissection were negative for metastatic tumor (15 nodes and submandibular glands were all normal). The hemimandibulectomy specimen was embedded in formalin and measured

7.0 x 3.5 x 2.2 cm in greatest dimension. There was no gross evidence of tumor on the external surface. A focus of mucoepidermoid carcinoma was found in the area adjacent to the socket of the extracted molar tooth (Figs 3 and 4). The anterior and posterior margins of resection were negative for disease. Extensive fibrosis and reactive bone formation was also noted.

No postoperative radiation therapy was given. The patient is now 2 years postsurgical resection and is free of tumor.

Discussion

There is no pathognomonic radiologic picture which distinguishes mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the mandible from other bone lesions. On x-ray examination a unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion is usually seen. Diagnosis is made only by biopsy.

54 American Journal of Otolaryngology, Vol 15, No 1 (January-February), 1994: pp 54-57

From the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Medical Center at Princeton, Princeton, Nj; and the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA.

Address reprint requests to David Goldfarb, DO, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Medical Center at Princeton, Princeton, NJ 08540.

Copyright© 1994 by W.B. Saunders Company 0196-0709/94/1501-0008

Lyme Disease: A Review for the Otolaryngologist

David Goldfarb, DO• Princeton, New Jersey Robert T. Sataloff, MDh Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Abstract

Lyme disease is an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of patients seen by the otolaryngologist. Facial paralysis is the most common sign. The otolaryngologist may also see patients with temporal mandibular joint pain, cervical lymphadenopathy, facial pain, headache, tinnitus, vertigo, decreased hearing, otalgia and sore throat. The incidence is increasing and known to be endemic to certain areas of the United States and abroad. This paper reviews the various ways Lyme disease appears to the otolaryngologist. Three cases along with a discussion including epidemiology, vector, animal host relationship, clinical manifestations and pathophysiology are included. The literature is reviewed and the treatment discussed.

Introduction

Lyme disease is not a new clinical entity but rather was recently recognized as one in the mid-1970s. 1 For many decades other names were given describing the condition of lyme disease, such as: Bannwarth syndrome, Garlin-Bujadoux syndrome, chronic lymphocytic meningoradiculoneuritis, tick borne meningoradiculoneuritis and erythema chronica migrans.2

In 1977, Steer recognized Lyme disease as a systemic disease and later described three stages.3 5 It wasn't until 1982 that Burgdmfer isolated spirochetes from the tick, Ixodes dammin i. 6 Johnson, in 1984, cultured Borrelia burgdotferi, a spirochete and identified antibodies to this organism.7·8 This led to the ability to serologically test patients in order to diagnose Lyme disease.9 Lyme disease is an important factor in the differential diagnosis of many patients seen by the otolaryngologist.

"Department of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery, Medical Center at Princeton, Princeton, New Jersey 08540.

Department of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107.

The purpose of this paper is to review and summarize the otolaryngologic manifestations of Lyme disease and to dis cuss its management. Review of 3 cases helps illustrate the clinical problems encountered commonly.

Case 1

The patient is a 45-year-old white man, who was camping in the woods of Maine, and noted a firm swelling in his right parotid gland, during which he also noted onset of fever, chills, malaise and myalgia.

One week after these symptoms started, he noted diffuse erythema on the right side of his face and neck from the level of the right zygoma superiorly to the level of the clavicle inferiorly and to the postauricular region posteriorly. He denied any tenderness. Initially he was started on cefadroxil for ten days. His symptoms and signs resolved until two days after completion of the cefadroxil. After a second course of cefadroxil the erythema and tenderness recurred again.

The patient was then evaluated by an otolaryngologist. A computerized tomography (CT) revealed a 2 x 2.5 x I cm. lesion in the right parotid consistent with inflammatory reaction. A few intraglandular and submandibular nodes were also noted. Several days later the patient noted some difficulty with mastication and closing his mouth. Within two to three days his problem with mastication had resolved, but he had trouble keeping his lips together. The next day the patient awakened with a right facial paralysis.

On reevaluation, the patient's facial paralysis was found to be incomplete. The marginal mandibular and buccal branches were more involved than the upper branches. Other cranial nerves were intact. No other neurologic findings were appreciated. The patient had a firm, tender, nodule two centimeters in diam ter and freely mobile, in the tail of the right parotid gland. There was no other cervical adenopathy. The patient was admitted to the hospital, lyme titers were drawn and he was started on ceftriaxone 2 grams IV ql2

Sinusitis, URI, Common Cold

There's A World Of Symptoms Out There...

Your prescription makes a world of difference!

References:

May RJ. Pharmacotherapy: A pathophysiologic approach. J Allergic Rhinitis

1989;945-947.

White WB. Drugs for cough and cold symptoms in hypertensive patients.

Case 2

The second patient is a nine year old boy with a history of having two ticks removed from his right temporal region one month earlier.

Three weeks after having these ticks removed, he developed fever, nausea and headaches which lasted one and a half weeks. No rash had been noted, possibly because the hair on his scalp camouflaged it.

The patient was initially treated by his pediatrician for otitis extema with drops and penicillin. He subsequently developed a complete right facial palsy. There was no history of drainage from either ear, vertigo, tinnitus, hearing loss or ear pain. Arthralgias in his knees, elbows and neck were noted. The patient had no known drug allergies. Past medical history and surgical history were negative.

His otitis extema had resolved, and his head and neck exam was normal except for posterior triangle lymphadenopathy and complete right facial palsy. No other cranial nerve abnormalities were noted.

The patient was started on amoxicillin 500mg PO four times a day and prednisone. Lyme titers and an MRI were ordered. Titers were positive for lyme disease. The lgM level was 87.0(normal <1), the lgG level was31.5 (normal <l)and the lgA level was 7.4. The elevated IgA level is associated with CNS involvement.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and internal auditory canals was carried out with gadolinium enhancement. Bilateral prominent posterior triangle lymph nodes were noted, but the study was otherwise normal.

Two days after starting the amoxicillin and prednisone the patient's facial function improved. The facial paralysis had completely resolved within one week of treatment. The steroids were weaned over a 7 day period. The antibiotic was continued for four weeks.

Case 3

A 52-year-old white woman, with a history of lyme disease 9 months earlier complained of bilateral hearing loss and ear pain, greater on the left. The left ear pain began first and the right side started two weeks prior to her initial visit. The patient was initially placed on amoxicillin 250mg twice a day by a primary physician. The antibiotic helped with the ear pain, and her hearing improved slightly. Some tinnitus was reported on the right, She had no vertigo and no otoffhea.

Examination revealed that the left tympanic membrane was normal, and the right was intact but dull. The Weber test was midline and the Rinne was positive on the left and negative on the right. Her nasal mucosa was congested and swollen. Her larynx, hypopharynx and nasopharynx were normal. There were no masses, bruits or tenderness in the neck. Hearing (using ANSI, 1969 ), was normal on the left. The right side showed a moderate sensorineural hearing loss. Stapeduis reflexes were absent on the left and present on the right at 70db (500hz), 85db(lK Hz) and 100 db(2K Hz).

The patient was treated with ceclor 250 mg three times a day for a total of ten days and blood was drawn for repeat lyme titers. On day 12, the patient stated that her hearing had improved. She was now complaining of pain in her knees, headaches and ameno IThea. She was started on doxycycline 100mg PO twice a day. Repeat audiogram was normal bilaterally. The lyme titers were positive. The IgM was 3.03 (positive>1), the lgG was 0.25 (Positive>1).

Epidemiology

Between 1984 and 1986 an annual incidence of fifteen hundred cases of Lyme disease was reported. This disease is known to be endemic in many countries including the United States, Europe, Australia, Switzerland and in Russia.11 The northeastern parts of the U.S where Iyme disease is particularIy common include: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Rhode Island.10

In the Midwest it is endemic in Michigan and Wisconsin; and in the west, in California, Nevada, Oregon and Utah.10 This disease is most common in the summer with 60% of cases occurring June through August. 2 12

Although only 2% of patients bitten by ticks carrying the disease develop a classic "bulls eye" shaped rash (erythema chronica rnigrans), almost 50% show significantly raised antibody titers. Lyme disease affects men, women and children equally.

Etiology

A spirochete, Borrelia burgdotferi, is the causative organ ism. The tick, genus Ixodes, is the primary vector. Ixodes dammini is more common in the Northeast, while Ixodes pacificus is more common in the West.10 13

The three main hosts are the white-tailed deer, white footed mouse and birds.14 Other investigators have noted certain insects and lizards to be hosts as well.9

The life cycle of the Ixodes tick is broken down into three stages: Larva, nymph and mature adult stage.14 Less than 5% of ticks are actually born infected. The majority get the infection during the larval or nymphal stage, when a blood meal is acquired from an infected host. The white footed mouse is the preferred host for the nymph in the summer. The white-tail deer is the preferred host for the adult.15 The larva sometimes acquire the spirochete during a blood meal from an infected host as well. If this occurs, the larva may become a host with the capability of spreading the disease to humans. If the larva does not acquire the spirochete during that blood meal, it may acquire the spirochete during one of its blood meals in either its nymph or adult stage. The nymph seeks its second blood meal the following spring, when humans are often bitten. The adults ai·e more active in the fall.

The nymph tick is very tiny, approximately 1 to 2 mm in size and its bite may go unnoticed. The adult is larger and more noticeable, approximately 4 to 5 mm in size.

Pathophysiology

The spirochete is transmitted through the tick saliva or fecal debris.13 After the patient is inoculated with the spirochete, universal dispersion occurs.

Evidence exists for three mechanisms of injury to the human body: 1) direct invasion, 2) direct immunological attack and 3) vasculitis. 16

Evidence for direct invasion has been demonstrated by the presence of the spirochete in skin, cerebrospinal fluid, blood, myocardium and joints.17 This may explain why certain patients develop meningitis, cranial nerve palsy, radiculopathies joint and cardiac effects. Evidence for direct immunological attack is suggested by the development of variable parenchymal abnormalities, immune complexes and immunoglobulins with complement that · have been found in biopsy specimens. Certain B cell alloantigens from the histo compatibility complex, HLA-DR4, HLA-DR2 have been noted to have an increased incidence in patients with Lyme disease.18

Vasculitis has been demonstrated on angiographic studies and may lead to injury to the vasanervosum with resulting axonal neuropathy.

As with Bell's palsy the location of the lesion can be quite variable with all segments noted topographically.

Considerations for the Otolaryngologist

The clinical course of Lyme disease is broken down into three stages.4 During stage one disease, erythema chronica rnigrans is reported in 60-80 percent of patients.12 18 This sign has been labeled the hallmark of stage one Lyme disease. The rash is characterized by a small expanding papule which forms an annular lesion with a central clear zone and an erythematous outer border.4 This erythematous outer border is produced as the spirochete migrates outward in the skin. These rashes can be found anywhere in the body. They occur initially at the site of inoculation of the spirochete.4

The lesions are usually warm to the touch and may be painful or have a burning sensation. The rash usually occurs within the first week with a range of three to thirty-two days.4 5 They may also develop multiple annular lesions secondary to erythema chronica rnigrans, and this is due to spread of the spirochete. The rash may occur simultaneously, with, before or after other signs and symptoms. 19

Other signs and symptoms are usually non-specific flu like symptoms such as malaise, fatigue, lethargy, headache, fever, chills, arthralgia, myalgia, anorexia, sore throat, cough, chest pain, abdominal pain, dizziness, photophobia, either generalized or regional lymphadenopathy, low grade fever, malar rash, backache, periorbital edema, conjunctivitis, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant tender ness and arthritis. 14

It is during stage 2 of the disease that patients see an otolaryngologist. In stage 2 of Lyme disease 15-20% of patients have been reported to develop neurologic complications.18 Stage 2 is broken down into neurologic, cardiovascular and cutaneous manifestations.

Facial paralysis is one of the most common otolaryngologic signs.2 2° Clark et al, in 1985 noted that 10.6% of95 l patients with Lyme disease had a facial paralysis. Of these, 22.8% were bilateral.2 Seventy-four percent of patients with bilateral facial paralysis were male. Overall frequency of facial paralysis was equal between males and females. Complete paralysis was noted in 60.2% of those with VII nerve involvement, and there was no correlation between the laboratory results and the severity of the palsy.

Clark et. al. found that 32 patients treated with antibiotics alone had a median time to recovery of 24 days. Likewise the patient group treated with both steroids and antibiotics had a median time to recovery of 24 days. They noted that while recovery time was slightly longer for patients with bilateral facial paralysis, the rate of recovery was the same regardless of the treatment. The group of 24 patients which received no treatment had a median time to recovery of 30 days. Other authors have suggested that antibiotic treatment does have a beneficial effect on recovery time.

It is important to note that any cranial nerve may be involved, and the cranial nerve involved has nothing to do with the site of inoculation. 17 Schroeter, 1988 reported a case of recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis secondary to Lyme disease.21 A forty-five year old healthy singer developed a sore throat and malaise followed 24 hours later by left vocal fold paralysis. The patient had positive antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi. After six weeks of treatment for Lyme disease her titers were markedly reduced, and subsequent laryngoscopy was normal.

Krejcova, 1988 described neurotologic symptoms associated with Lyme disease.22 Forty-four percent of his patients had hearing abnormalities and 81% had vestibular abnormalities. Of his patients, 38% had either hearing or vestibular migrans is still present, or weeks later; and, if untreated, they can last months.

Lymphadenosis benigna cutis, also known as Borrelia lymphocytoma, is a cutaneous lesion usually seen during stage 2 disease. This skin lesion is characterized as a dense lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis and/or subcutaneous tissues.19 This lesion may appear anywhere on the body, and may not develop for six to ten months after the tick bite. This lesion is said to have a tumor -like bluish red swelling or nodular appearance which is usually accompanied by a regional lymphadenopathy.19 These patients generally have increased levels of IgG against Borrelia. If untreated, these lesions may last for many months. 19 Awareness of this lesion is important to the otolaryngologist, especially when a patient has a nodular neck mass. Failure to recognize this lesion may result in increased morbidity to the patient and subsequent progression of the disease.

Stage 3 usually occurs weeks to years after tick exposure.

Approximately 60% of untreated patients have been reported to go on to Stage 3 disease.2 The patient may see the otolaryngologist complaining of temporo-mandibular joint pain.2 This is often the first joint affected and the patient may give a history of intermittent attacks lasting weeks to months.2 Arthritis has been reported in 67% of untreated patients. Usually the large joints are involved primarily. The knee, hip, shoulder, ankle and elbow are most commonly involved.10

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans is a cutaneous manifestation found generally in stage 3 of Lyme disease.19 It is most commonly seen in elderly patients and consists of inflammatory and atrophic phases.

The inflammatory lesion is characterized by a bluish-red discoloration which usually starts on an extremity. It can last for years. This inflammatory phase gradually becomes replaced by atrophy of the skin and underlying bone and joints. It is important to recognize these lesions as these patients are often misdiagnosed as having venous or arterial insufficiency or scleroderma.

Diagnosis

Patients with Lyme disease have non-specific laboratory findings such as elevated sedimentation rates(ESR) and white blood cell(wbc) elevation. More diagnostic findings include positive biopsy, cultures or positive serologic testing. While the spirochete has been isolated from several areas of the body, (blood, cerebrospinal fluid, skin, joint fluid, myocardium and epineurium), serologic testing remains the mainstay of laboratory diagnosis.9 16 17 abnormalities as their first neurologic symptom. Fifty per cent of these patients also had facial paralysis. Other associated neurologic findings included diminished concentration ability, ataxia, poor motor coordination, irritability, head aches, chorea, encephaliti s, cerebellar ataxia, motor and sensory radiculopathies and mononeuritis multiplex. All of these findings may arise while the erythema chronica

Cultures for growing Borrelia are very expensive and have a short half-life. The most common assays are immunofluorescence antibody (IFA) and Elisa tests. The Elisa test is more sensitive and specific.16 IgG takes six weeks to become elevated and therefore is useful primarily in assessing stage 2 and 3 disease. IgM, while less specific, is more useful in the early stages of Lyme disease when infection, reinfection and reactivation are suspected. Case 3 demonstrates the potential for reactivation or reinfection.

False positives have been seen in mononucleosis and rheumatic disease.10•16 False negatives may be seen in patient s who have received antibiotics during the early course of the disease, blunting the antibody response.

Unlike acquired syphilis, VDRL is negative; and rheumatoid factors are negative. Another way to distinguish rheumatoid arthritis from Lyme disease is the lack of morning stiffness and lack of subcutaneous nodules.13

While serologic testing remains the best method of establishing a diagnosis, only 50% of patients with stage 1 disease are positive. Direct detection of the spirochete is very difficult, requiring a thousand spirochetes per milliliter of blood and special facilities.11 If biopsies are to be taken, it is best to take the biopsy from the leading edge of the skin lesion, the region where spirochetes are most likely to be found. 1

Treatment

In stage 1 disease for adults, oral tetracycline or doxycycline is usually effective in clearing the disease and preventing progression to later stages. 18 2324 Tetracycline 250 mg orally four times a day for 10-30 days or doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day for 10-30 days is recommended.1 8 Doxycycline may be preferred over tetracycline because it is only given twice a day and has better soft tissue penetration. In adults with intolerance or allergy to tetracycline, amoxicillin 500 mg four times per day over 10-30 days is recommended.18 For children less than eight years old penicillin or amoxicillin is preferred. Amoxicillin 250 mg three times a day, or 20 mg per kilogram of body weight per day in divided doses, should be used for 10-30 days.18 For children less than 8 years of age with penicillin allergy, erythromycin 250 mg three times a day, or 30 mg per kilogram per day in divided doses, for I 0- 30 days is recommended.18 For cranial nerve involvement such as facial paralysis, oral tetracycline or doxycycline as outlined above is recommended for 15-30 days. If no response is seen then IV medications should be tried. Ceftriaxone 2 grams IV per day for 14days is useful for other neurological abnormalities as well since it penetrates the blood brain barrier better than penicillin.18 In cases of allergy to cephalosporin or penicillin, doxycycline or chloramphenicol may be use d. For cardiac abnormalities of low degree, oral regimens may suffice. For high degree heart block, ceftriaxone or penicillin IV is recommended.

Progression to stage 3 disease is more common in patients who have had a severe stage 1, but may follow mild stage 1 disease which was left untreated. In such cases oral medication is tried for 30 days; and, if it fails, IV penicillin or ceftriaxone should be used. 18

Conclusion

Although facial paralysis is the most common sign of Lyme disease seen by the otolaryngologist, numerous other otolaryngologic symptoms and signs may be caused by this entity. Facial paralysis, if treated early, and other cranial nerve palsies due to Lyme disease have a good prognosis. Early antibiotic treatment is recommended to prevent late complications, and prolonged follow-up is advisable.

Because of its varied appearance and increasing incidence in the United States, the otolaryngologist must be aware of Lyme disease and be prepared to recognize and treat this multifaceted and highly responsive malady.

References

I. Steere, AC, et al: Th e Spirochetal Etiology of Lyme Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 1 98 3; 308:233-240.

Clark, JR, Carlson RD, Sasaki CT, et al. Facial Paralys is in Lyme Dise ase. Laryngoscope 1985; 95: 1 34 1- 1345.

Steere, AC. The Clinical Evaluation of Lyme Arthritis. Annals of Internal Medicine 1987; I 07:725-73 I.

Steere, AC, Malaawis ta SE, Hardin JA, et al. Erythema chronicum migrans and lyme arthritis: the enlarging clinical spectrum. Ann Intern Med 19 77; 86:685-98.

Steere, AC. Pathogenesis of Lyme Arthritis Implications for Rheumatic Disease. Annals New York Academy of Sciences 19 8 8; 87-92.

Burgdorfer, WA, Barbour AG, Hayes SF, et al. Lyme Disease - Tick-Borne Spirochetosis. Science 1 982; 2 I 6: I 3 I 7 -13 I 9.

Johnson S, et al. Lyme Dis e ase: A Selective Medium For Isolation of the Suspected Etiological Agent A Spirochete. J Clin. Microsc 19 84; 19:81- 83.

Mertens HG, Martins R, Kohlhepp W. Clinical and Neuroimmunological Findings in Chronic Borrelia Bungdorferi Radiculomyelitis (Lyme Disease). Journal of Neuroimmunology I 988; 20:309-3I 4.

Barbour, AG. Diagnosis of Lyme Disease: Rewards and Perils. Annals of Internal Medicine I 989 ; 11 (7):50 1-50 2.

10. Center s For Disease Control. " Lyme Disease - Connecticut ". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Jan 1 98 8, 37: I, pp. 1- 3.

11. Barbour AG. Laboratory Aspects of Lyme Bone liosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 1 988; 1 (4 ):399-14.

12. O'Neill PM, Wright JM. Lyme Disease. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 19 88; 40:284-293.

13. McKenna OF. Lyme Disease: A Review for Primary Health Care

Providers. Nurse Practitioners 1 989; 1 4 (3): 18-29.

14. Finkel MF: Lyme Disease and its Neurologic Complications.

Archives of Neurology 1 988; 45:99- 104.

15. Hamilton DR. Lyme Disease - The Hidden Pandemic. Post Graduate Medicine 1 989 ; 85(5):303-314.

Magnarelli LA. Serologic Diagnostics of Lyme Disease. Annals New York Academy of Science 1988; 539:154 -1 6 1.

Si g al LH. Lyme Disease, I 988: Immunologic Manifestations and Possible Immunopathogenic Mechanisms 1989; 18 (3):151-1 67.

Steere AC. Medical Progress-Lyme Disease. New England J Med 1 989; 32 1(9):586-594.

Asbrink E, Hovmark A. Early and Late Cutaneous Manifestations in

Ixodes-Bo rne Borreliosis (Erythema Migrans Borreliosis, Lyme Borreliosis). Annals New York Academy of Sciences 1988;539:4-1 5.

Glasscock ME, Pensak ML, Gulia AJ, et al. Lyme Disease: A cause of Bilateral Facial Paralysis. Archives of Otolaryngology I 985; 111:47-49.

Schroeter V. Paralysis of Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve in Lyme Disease. Lancet I 988; 1 245.

Krejcova MB, Bojar M, Jerahek J, et al. Otoneurological Symptoma

tology in Lyme Disease. Adv Otorhino Laryn 1988; 42:210-212.

Neu HC. A Perspective on Therapy of Lyme Infection. Annals New York Academy of Sciences 1 988; 539 :3 1 4-3 1 6.

Skoldenberg B, Stiernstedt G, Karlsson M, et al. Treatment of Lyme Borreliosis with Emphasis on Neurological Disease. Annals New York Academy of Sciences 1 988; 317 - 323.

Volume 73, Number 11 829